I’m Alexis Madrigal. I’m working on a book about how Oakland has been shaped by great floods of money and power. It’s a crossroads. Railroad, highway, ocean. Tectonic plates. Social movements. Racial groups. Ideologies.

The life of Margaret Gordon, an environmental justice leader in West Oakland, is the spine of the book. The setting is 7th Street, where the port connects to the city, and once the beating heart of the black community of the East Bay. So, it’s both a history of one black woman’s Bay Area, and a sweeping examination of the development of urban America. Because the questions that power this book are not only at play in Oakland. Racialized capitalism drives the development of cities, and cities drive the creation of wealth for most Americans through the property they own in them. At the same time, globalization, powered by software and containers, has run a cargo ship through the former raison d’etre for cities: making things and housing the people who made stuff. What are cities becoming when the big money is made inside a screen or manufactured somewhere in Asia? What is a city for? And what does a city owe to the residents who have made it what it is?

That has led me to dig deep into the history of this city that I love. The quest to gather receipts has taken me all around the region just trying to understand what happened to 7th Street, to West Oakland, to Oakland, to the Bay. I now have a trove of documents that I’d like to share with people who are a part of all these communities that come from our libraries and museums.

Time and again, doing this work, I’ve been struck by the power of the primary source. It’s one thing to hear that black and mixed neighborhoods were targeted for financial disinvestment and demolition, but it’s a whole other thing to see the plans laid out in government documents, supported by academics, and encouraged by the press.

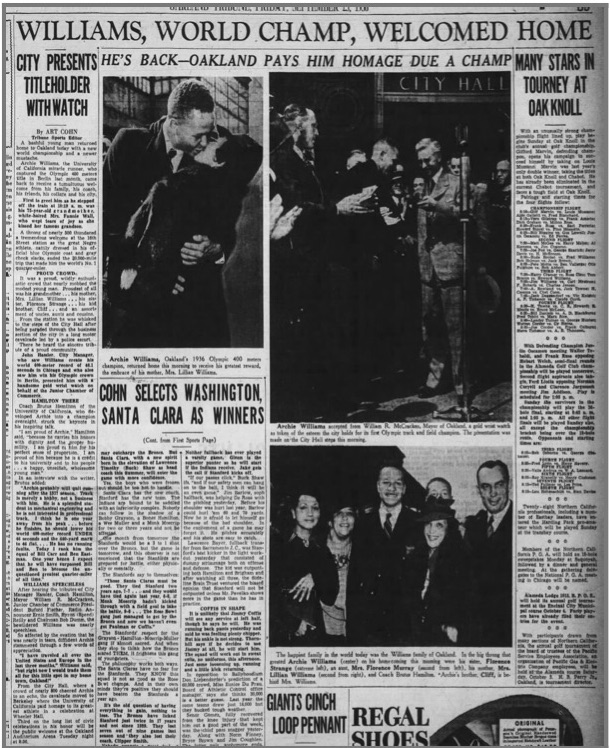

For example, Oakland-born Archie Williams won an Olympic gold medal in 1936, part of a group of American black men who dominated the games that Hitler hosted in Berlin. His father died young and he lived with his mother and grandparents on Telegraph Avenue, part of Oakland’s small but rising black middle class. His grandmother founded an orphanage for black children—and was a dedicated clubwoman who knew the mayor personally. His grandfather was a veteran. He was not only an Olympian, but also an engineering student at Cal. When he returned from Europe, he was literally paraded through town. “I have traveled all over the United States and Europe in the last three months,” the Oakland Tribune reported Williams said, “but right now I would trade them all for this little spot in my home town!”

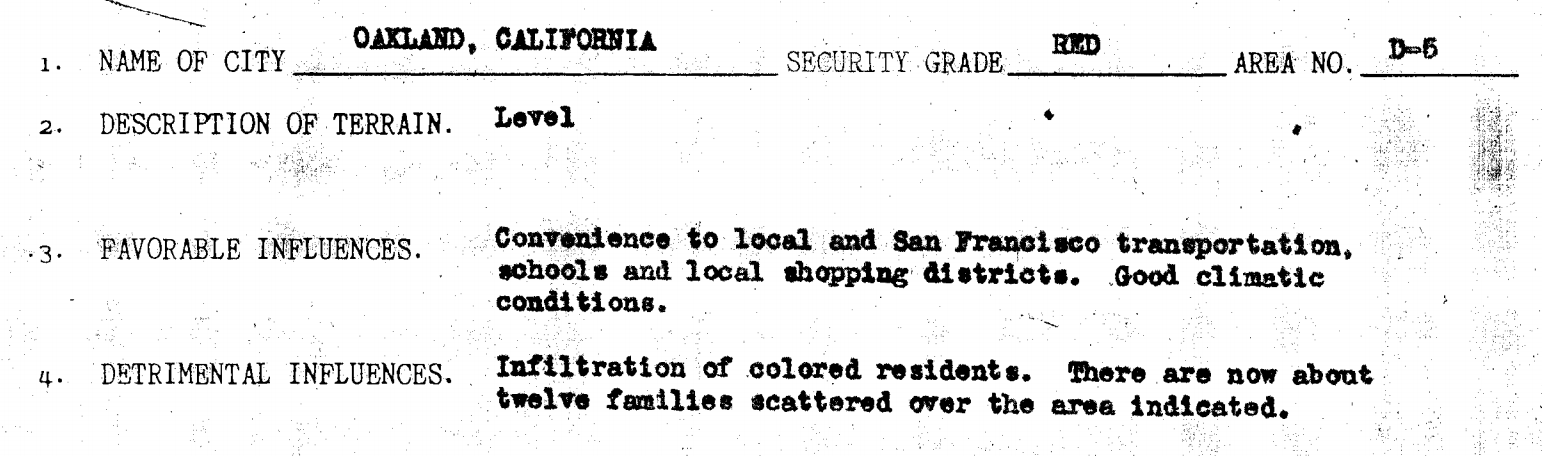

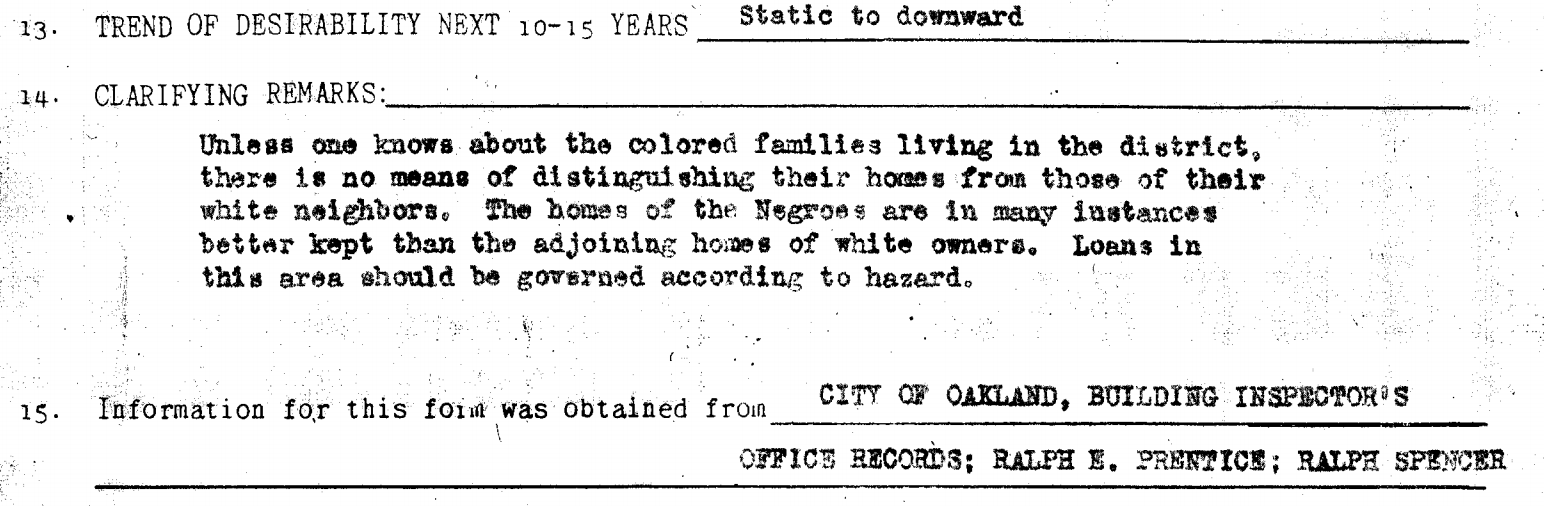

And during the exact months when he was preparing for the Olympics, the Federal government, with local assistance, was evaluating his neighborhood in north Oakland as a place where the government would make or back loans. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation hired people across the country to make maps that would help banks understand the risks facing the mortgages they’d underwrite. Two men, both named Ralph, who were part of the local real estate establishment, wrote a short report on Williams’ neighborhood, which marked the area a risky investment, assigning it a security grade of “Red.”

Archie Williams’ family was one of the 12. The Ralphs included a set of “Clarifying Remarks,” which I ran across five years ago now, and which are never far from my mind.

The Williams family were the best Oakland had to offer. But when the government looked at them, what did or could it see? Negro, infiltrator, detrimental influence, bringer of instability, property value destroyer. Imagine Archie working in the yard, back from Berlin, cutting the hedges, weeding, planting flowers. Imagine the Ralphs walking by, maybe they even had a nice chat. “Congratulations, son!”

But they were black. The map would be red. The shared understanding at the local and national levels was: any racially mixed area is marked for disinvestment.

Not every document contains a story quite like this, but my hope is that by putting the archive out there, it will make it easier for other people to do this kind of excavation, uncovering the real history of the places we live. Many black people in Oakland know what happened, the core truth of it, if not every detail about the demolition, the disinvestment, police brutality, the construction of the highways, the Knowland political machine, the environmental racism. Most other Oakland residents don’t. This is a city that as late as 1964 voted overwhelmingly against a Fair Housing law, as did the rest of the state. My hope is seeing the receipts across time helps everyone here come to a shared understanding of how the city was built.

Many thanks to the Oakland Public Library Oakland History Room, UC Berkeley’s Environmental Design Library, and Bancroft Library, the African American Museum and Library at Oakland, the Oakland Museum of California, SF State’s Labor Archives and Research Center, the Internet Archive, the San Francisco Public Library History Room, the Richmond Historical Museum, the Rosie the Riveter National Archives, the Prelinger Library, BART Archives, Port of Oakland, the National Archives at College Park, and the National Archives at San Francisco, which are really in San Bruno behind a mall and some condos.

As the list above shows, this is not a comprehensive accounting of everything in the Bay. But I hope the idiosyncratic piles that I’ve driven out into the liquid (and rapidly disappearing) local history can undergird broader efforts to bridge past and future.

If you have questions, have a document to add, or a story to tell, get in touch with me at alexis.madrigal@gmail.com.

(Oh, and if it’s not obvious, this is a real work in progress, both the site and the book. Expect change.)