Most of my research has been in Oakland. Many of these documents have been digitized by my own hands, which unfortunately, you will see throughout these PDFs. Here, I’ve organized them roughly chronologically., and tried to give some background on how the document fits into the area’s history of race and housing.

- 1937: Oakland Real Property Survey

- 1937: Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Residential Security Map

- 1938: Need for a Low-Rent Housing Project

- 1939: A Year of Planning in Oakland

- 1945: Land Use Inventory of the Light and Heavy Industrial Zones

- 1946: Oakland Zoning Laws

- 1949: East Bay Civil Rights Congress Report on Police Brutality

- 1949: Redevelopment in Oakland

- 1952: Shoreline Development

- 1956: Residential Area Analysis

- 1964: Housing Discrimination in Oakland

- 1964: Port of Oakland Annual Report

- 1966: Internal Postal Service Memos About Oakland’s New Post Office

1937: Oakland Real Property Survey

In 1936, the Oakland City Planning Commission submitted an application to the Works Progress Administration for Federal help in preparing a “Real Property Survey.” I.S. Shattuck, then Oakland’s city planning engineer, directed this substantial task involving “supervisors, field foremen, field enumerators, and office employees” that took most of the fall of 1936. Shattuck held that the importance of the survey “can scarcely be over-emphasized.”

Housing was at the root of many of the issues of a growing city, and “to remedy existing conditions, definite and accurate information must, first of all, be made available.”This report Shattuck submitted contained that information. Data was amassed on every single block of the city: Total number of dwelling units, percent of residential structures built in 1919 or before, percent of dwelling units owner occupied, percent of residential structures needing major repairs or unfit for use, number of structures having business uses, percent of dwelling units with no private bathroom, percent of families that are non-white (negro or oriental). The report would be “the basis for choosing districts where existing conditions are the worst, and undertaking for these districts more intense studies dealing with suggestions for bettering existing housing,” Shattuck wrote, “and even, in some cases, for replanning the physical appearance of these districts in conjunction with a program of clearance and rehousing.”

“These districts” meant West Oakland, particularly the racially mixed western part of it. As the area had been zoned for heavy industry, despite its large residential populations, Shattuck was sure that West Oakland’s housing units would decrease as businesses took property from residences. This “crowding out” would help get rid of some of Oakland’s bad housing, but he admitted, “living conditions in the dwellings remaining will certainly fall further and further below a decent standard.” This admission should be astonishing: the city intended to displace some people and hurt those who remained. But that was not Shattuck’s only plan. He also suggested that a freeway be cut right through the heart of West Oakland, creating an infrastructural division between the mixed-race (western) and white (eastern) parts of the neighborhood. “The housing advantage of this diagonal highway route is that it would segregate that portion of the district under discussion where non-white families are largely concentrated from the portion where they are relatively few in number,” Shattuck argued. “A plan of housing could take advantage of this physical division by providing a unit or units for mixed race occupancy west of the East Shore Highway, and units for all-white occupancy east of the highway.”

The data from this report also was used in the Federal Housing Administration’s discriminatory approval of mortgage insurance. I found stacks of maps produced by local Oakland officials in the National Archives FHA map collection at College Park, Maryland

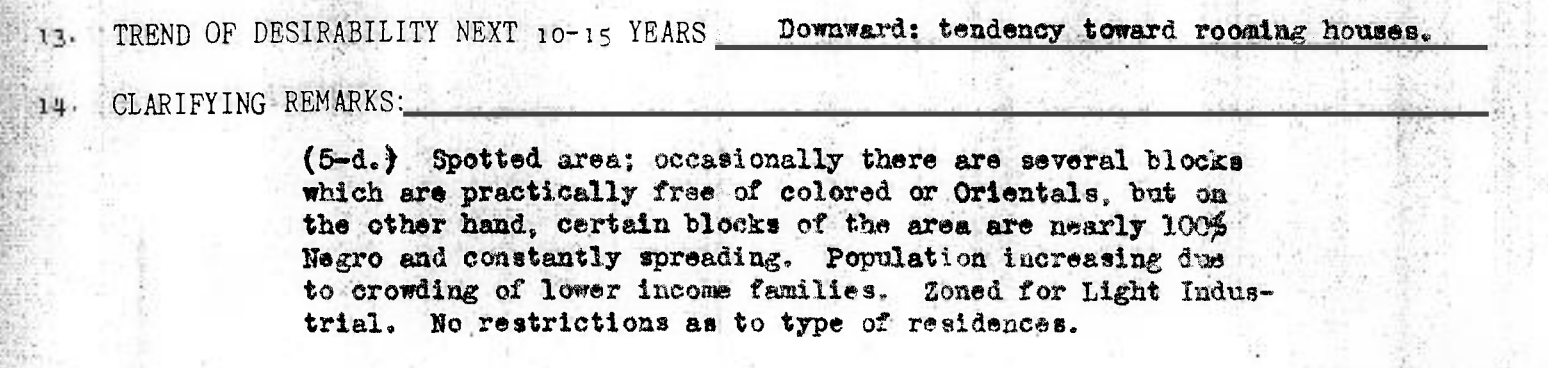

1937: Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Residential Security Map

If you’ve ever heard of a redlining map, this is probably what you were thinking of, or someone was describing. In the mid-1930s, a division of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation “residential security” maps of dozens of cities around the country. The HOLC maps put racial “infiltration” at the center of their analyses of city conditions.

The lowest grade neighborhoods were shaded in red and described as “characterized by detrimental influences in a pronounced degree, undesirable population or infiltration of it.”

If you missed that, it’s worth noting that the Federal government organized a massive project covering every district in a major city in America that explicitly referenced the “infiltration” of “Colored” and “Oriental” people as both a cause of and proxy for neighborhood decline.

The maps were produced by HOLC employees with the help of local real estate guys. These people had been indoctrinated into a way of thinking about cities that saw racial conflict over neighborhoods as both inevitable and bad for home values. Drawing on the so-called “ecological” theories of the Chicago School of sociology, the “invasion” or “infiltration” of an all-white neighborhood by black people, in particular, was seen as a very bad thing. In Oakland, this training came directly from Frederick Babcock, who wrote the underwriting manual for the Federal Housing Administration.

Each section of the map was accompanied by a data sheet that had a short paragraph worth of “clarifying remarks.” In them, as in this example below, you see obvious racism in play. These maps became justifiably famous when Kenneth Jackson rediscovered and wrote about them in his classic book, Crabgrass Frontier.

It’s worth noting that scholars like Amy Hillier feel that these maps have been overinterpreted. First of all, the definition of redlining is supposed to be that no loans are made in an area; the redlined area is off-limits for real estate capital. But the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, in fact, made many loans into areas that are marked red on the map. They also note that the maps were not widely distributed and that it’s possible they had a limited practical effect on cities.

But more recent scholarship by Louis Lee Woods, II has called attention to the HOLC’s role as a model lender and appraiser within its home agency, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. The FHLBB had been created to encourage sound lending practices, and they pointed to the HOLC’s techniques as the gold standard to which all the banks that the Feds supported should aspire. If the maps themselves were kept under close watch and not widely distributed, the FHLBB described and promoted the use of these maps to other lenders through its in-house publication, the Federal Home Loan Bank Review. At least some banks did make similar maps. Bruce Beasley, a white artist who moved to West Oakland in the early 1960s, told me about going to a local bank to ask for a loan; the banker literally showed him a map with West Oakland outlined in red.

Scholars continue try to estimate how significant the HOLC maps were versus the banking industry’s preexisting practices. My research in Oakland, however, shows that the HOLC’s ground troops were part of the local real estate apparatus, and had trained on what would become the FHA’s appraisal methods. The racist machine can’t be easily pulled apart, and blame easily apportioned, because at a local level, it was all the same group of people.

If you want to really go deep, two academic projects cover this terrain in great detail: T-RACES and the University of Richmond’s astonishing Mapping Inequality. You’ll be able to find your neighborhood and substantial scholarship about what these maps mean.

1938: Need for a Low-Rent Housing Project

The Housing Act of 1937, known commonly as the Wagner-Steagall Act, was signed by FDR. It created the first public housing program, organized under the U.S. Housing Authority, which could make grants to local authorities to bulldoze” “substandard” housing and rebuild public units. Many states, including California, passed legislation that allowed cities to create local housing authorities, and so in Oakland, that became a question to be answered.

The new U.S. Housing Authority meant the possibility of grabbing a slice of the $500,000,000 in Federal funds dedicated to slum clearing and public housing. All they’d have to do was pay 10 percent of the upfront costs and 20 percent of the subsidy necessary to bring the rents in new housing within reach of poor people. But, first, the city planning department had to prove that Oakland needed “slum clearance” funds.

Oakland was at a disadvantage for getting Federal dollars. It was “a young city” that did not show “the more acute manifestations of ‘slums’ found in Eastern cities.” Did the Oakland of 1938 even have slums? City Planning Engineer John G. Marr drew on a Harvard University Press publication, Slums and Housing, for his definition: “The slum is a residential area in which housing is so deteriorated, so sub-standard, or so unwholesome as to be a menace to the health, safety, morality, or welfare of the occupants.”

By this definition, “Oakland does not have slum areas,” Marr admitted, “but it is evident that there is much bad housing to be found in the city.” More importantly, other areas were “definitely on the downgrade,” and so the “revivification of certain of those areas of incipient decay is essential.” Drawing on the Real Property Survey that fueled the HOLC and FHA’s risk-rating, Marr assembled data on Oakland’s bad housing in an “attempt to eliminate all emotional arguments so frequently resorted to in an attempt to justify an improvement in the housing of persons of low income.”

The upshot of this report was the creation of the Oakland Housing Authority and the construction of Peralta Villa and Campbell Village in West Oakland and Lockwood Gardens in East Oakland.

1939: A Year of Planning in Oakland

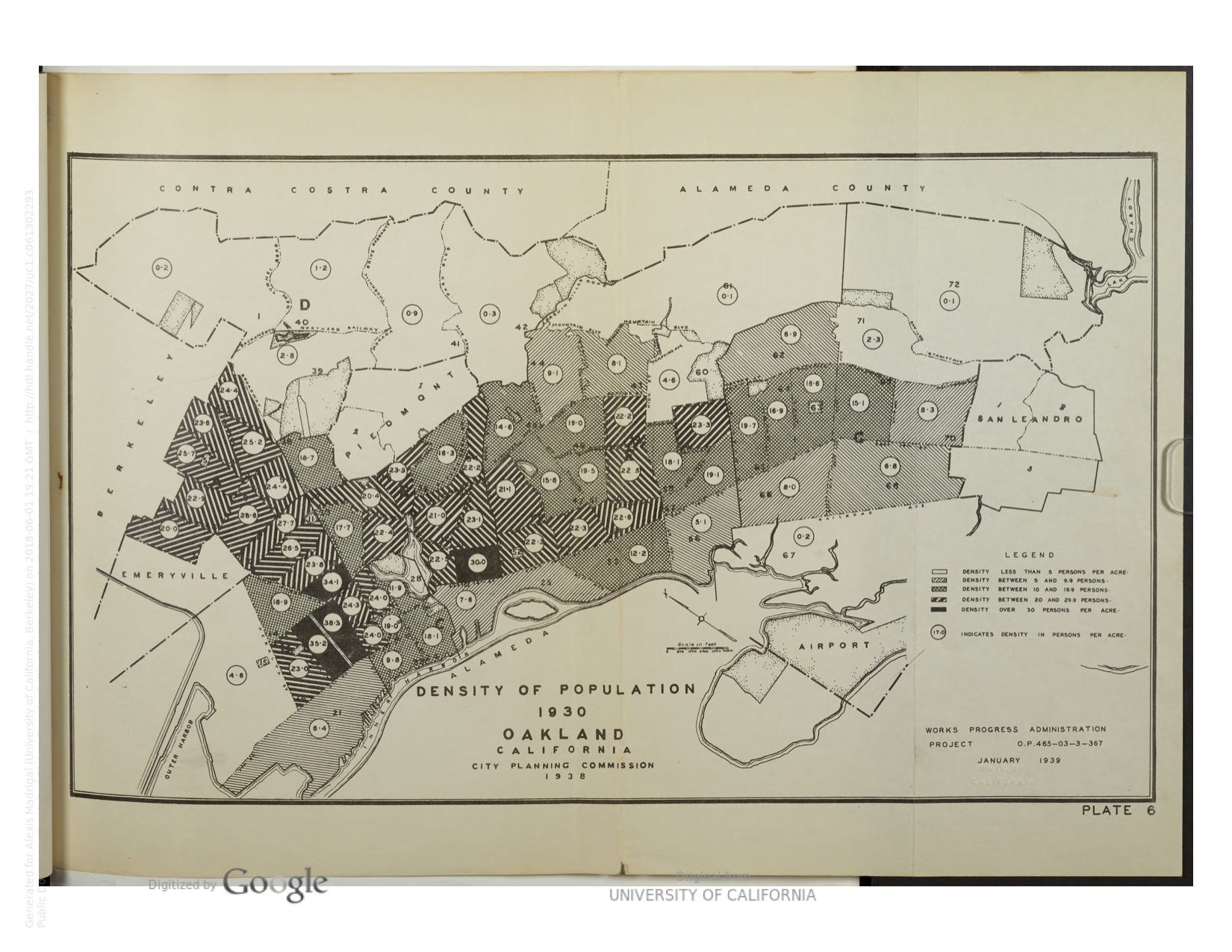

This is basically a book report on what the employees of the Works Progress Administration did for Oakland. It’s interesting primarily because it sets the scene in Oakland just before the influx of migrant war workers. Oakland is about 1.3% black in 1930. It’s a medium-sized, mostly white city, which had experienced substantial migration from Europe, which has begun to subside. West Oakland is the densest part of the city.

The report demonstrates that city planners did not see the influx of black southerners coming. As far as they were concerned, the small black population was going to remain small. “The non-white portion of the population represents only a small fraction of tho total city population today. It is not expected that there will be much change in this relative proportion in future years,” the report’s authors held. “There are numerous social and economic problems incident to this racial division which are deserving of special consideration and study so that an equitable solution can be achieved.” That was a bad prediction.

By 1944, the city’s black population stood at 21,770. Most of the newcomers were move from Louisiana, Texas, Arkansas, and other southern states. According to Gretchen Lemke-Santangelo’s Abiding Courage: Most Bay Area migrants were families who had kids, as well as young couples planning to have children. The black population grew rapidly, and white people left the city for the subsidized all-white suburbs. By 1970, almost 35% of Oakland’s residents were black. By 1980, that number would peak at 47%. (In 2010, black people made up only 28% of the city — and their numbers continue to fall.)

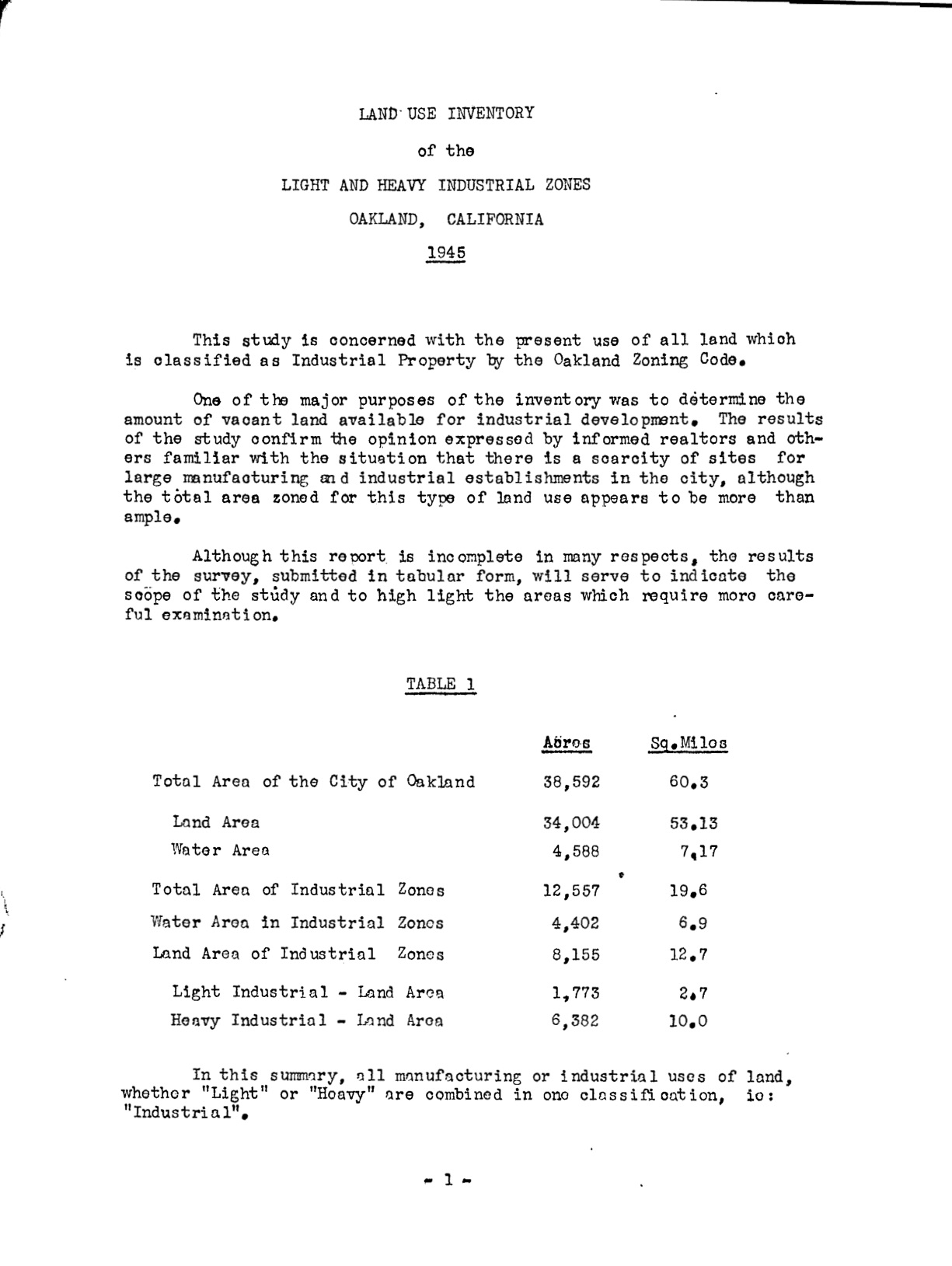

1945: Land Use Inventory of the Light and Heavy Industrial Zones

This short report from the end of the war reveals the anxiety of city planners in Oakland that they simply did not have enough industrial land available in the big chunks that companies supposedly wanted. City planners imagined that they could lure companies back if only they had the right type of land available for them. What’s important about that is that it provide a motive for cities to try to clear mixed industrial and residential areas of homes. And who had been forced to live in those polluted areas? Non-white people.

“The results of the study confirm the opinion expressed by informed realtors and others familiar with the situation that there is a scarcity of sties for large manufacturing and industrial establishments in the city,” we read, “although the total area zoned for this type of land use appears to be more than ample.”

The city saw two ways of increasing industrial land: filling in the Bay (which it did substantially) and “redevelopment of those areas in which the condition of blight is most advanced.” Blight became what I call the “password to plunder” mixed race neighborhoods, bulldozing them for civic projects and targeting them for polluting industries. The destruction served a dual purpose: it let the city do what it wanted with the least possible political resistance and it helped drive residents out of the areas that the city wanted to redevelop for industry. This isn’t a conspiracy theory so much as what city planner I.F. Shattuck admitted in his 1937 report referenced above.

1946: Oakland Zoning Laws

Oakland passed its first comprehensive zoning plan in 1935. This document shows the Oakland zoning laws as they existed in 1946, after 11 years worth of revisions. Nationally, zoning became a powerful way both to keep black people out of white residential neighborhoods and to concentrate profitable, polluting business in the areas of town where black people were able to find housing.

In the 1910s, hundreds of cities rushed to adopt zoning laws of some kind, even though no one was quite sure if they were legal. Oakland created an industrial zone in West Oakland in 1912, then barred businesses (and apartment buildings) in residential districts near Lake Merritt in 1918. After a series of state Supreme Court decisions, the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of zoning in the landmark 1926 case, Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company. Thereafter, the Federal Housing Administration required that cities develop comprehensive zoning plans in order to access mortgage insurance.

“Zoning’s founders fashioned a powerful new rationale for residential exclusion: the claim that exclusion of any ‘incompatible land use,’ be it apartments, factories, or occupancy by black people, was motivated not by ideology but by economics,” summarized David Freund in Colored Property.

Federal officials kept locals disciplined about the enforcement of zoning, as Oakland racist Real Estate Board reminded city officials in a late 1930s letter. “You will recall that at the time the Zoning Ordinance was being considered, Federal Housing Administration was keenly interested, and that, as a first result of your adoption of the ordinance, many thousands of Oakland residence properties were promptly made eligible for FHA mortgage insurance; properties which had not previously been eligible and would not now be eligible for such insurance but for this ordinance,” the letter began, before unveiling a barely hidden threat from the FHA. “We have recently been advised by an officer of Federal Housing Administration that that institution is again watchfully observant of Oakland’s official attitude toward the Zoning Ordinance, and is appraising the sincerity with which it is maintained.”

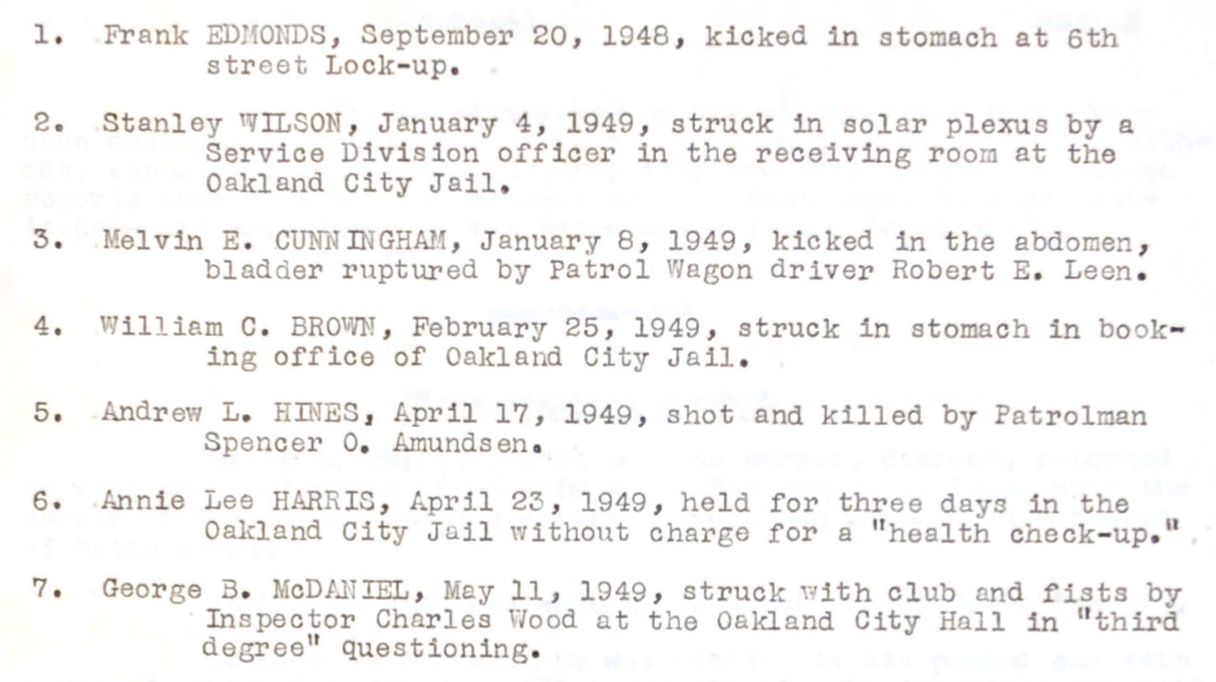

1949: East Bay Civil Rights Congress Report on Police Brutality

Oakland’s police force had a reputation for violence against black people that intensified as the number of African Americans in the city grew. In 1949, the East Bay Civil Rights Congress was both a Communist front group as well as the primary documenters of the conditions under which black people were living in the East Bay. Their leader was Decca Treuhaft, aka Jessica Mitford, a British royal who later penned the bestseller The American Way of Death.

Mitford provides a lively narration of her time with the Civil Rights Congress and Communist Party in Oakland in her memoir, A Fine Old Conflict. She pops up in Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law, defending the Gary family from a white mob in a Richmond housing development. Suffice to say: unlike local government officials, the local communists of the CRC were deeply embedded in the community and addressing real community concerns from housing discrimination to policing.

This report documents seven different incidents of police brutality, ranging from a policeman shooting Andrew L. Hines to several cops roughing up Stanley Wilson after they saw his wife was white.

“Such occurrences are responsible for the development of a state of tension among the Negro residents of West Oakland which, unless swiftly corrected, can have dangerous repercussions upon the entire community,” the report maintains. It is not surprising that the Black Panther Party was strongest in precisely this part of town.

“Oakland has the second largest Negro Population west of the Mississippi River. In some ways it is the center of Negro life and activity on the West Coast,” the report concluded. “Yet the Negro citizens of Oakland live in mortal fear of the Oakland Police Department.”

At the end of the report, they appended the findings on police brutality of the Mayor’s Committee for Civic Unity. As you might expect, they less harsh in their criticisms of officers, recommending that Oakland “be among the forefront of those communities seeking to creatively solve this problem.”

1949: Redevelopment in Oakland

This report was a bombshell in its day. It led to the largest city council meetings Oakland has ever known and played into statewide and national battles over real estate policy. There were two components that proved contentious: one, the designation of some areas of the city as “blighted” and two, the recommendation that public housing units be built. Both drew fierce opposition, but perhaps for different reasons.

In April of 1948, the city council tasked city planning engineer John G. Mar to work up a new report on the redevelopment possibilities in Oakland. The city had undergone tremendous change. There were almost 100,000 more people. Many of them were black, and they were crammed into West Oakland. And many black people were living in temporary war housing, which had intentionally been built to fall apart, everyone agreed. It was “Oakland’s sorest blight problem.”

Those who were in actual houses or apartment buildings found themselves in increasingly crowded surroundings. Adding a lot more black people into a segregated housing market meant higher and higher densities in the black parts of town. This made for a lively 7th Street corridor and a bustling black business community, but it also left the area open to quantitative attack. The more black people who arrived in West Oakland, the easier it would be for city authorities to prove that the neighborhood was in decline, by their metrics.

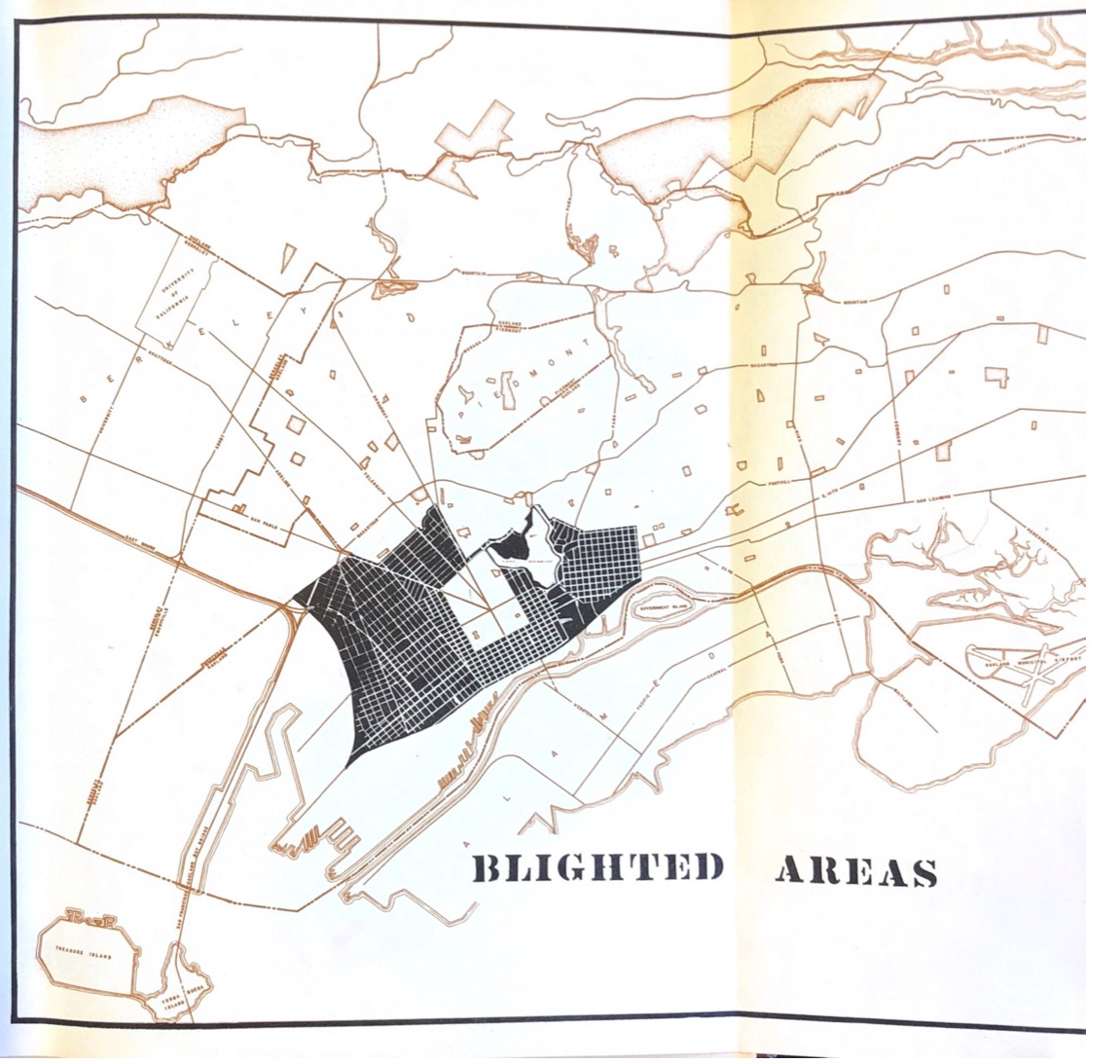

Over the next year, Marr worked on the report. When it came out in August 1949, it set the city aflame. The report is simple. The key takeaway is on the very first interior page: a map designating in black a crescent of BLIGHTED AREAS surrounding the downtown business district and Lake Merritt. Substantially all of West Oakland is included in the designation.

Marr saw blight, reflecting the discourse of the time, as an ineffable but powerful force in the city.

“Blight is not a condition which can be directly observed or defined. It is a complicated pattern caused by many related conditions and exhibiting interdependent symptoms.” It began with shoddy building, which led the people who could afford to to leave. As the rents it was possible to extract fell, property owners stuffed more people into the same buildings. That crowding and the poverty of the people living there “lead to tuberculosis and other diseases. The death rate climbs.” From there, the spiral down accelerated.

“Business, industry, and dilapidated residences are indiscriminately mixed. Family unity is disrupted. The step from there to juvenile delinquency is short; shorter still is the second step into crime. And who can put his finger on a single cause for all this degradation? There is no single cause. The interaction of a great many forces produces blight. Therefore, the acid test of blight is to find where most or all of these traits occur simultaneously.”

From Redevelopment in Oakland

His method tracks right back to the University of Chicago School of Sociology Map Room. On a base map of Oakland, Marr gathered spatial data—by census tract—about population density, age of dwelling, bath facilities, buildings in disrepair, monthly rents, number of tenants, crowding, fires, juvenile offenders, serious crimes, tuberculosis deaths, and infant mortality. He split each set of data into 6 buckets, and assigned them each progressively darker shading, the bottom tranche getting solid black. The grading was, so to speak, on a curve: the census districts were ranked relative to others. There had to be some tracts on the bottom, regardless of their absolute conditions.

He laid out all his data on a single chart. Across the top, he put all the different “characteristics of blight” and along the left, he placed the census tracts in order. One glance at the visualization tells the story: there is a thick, mostly black section from about census tract 11 to 29. In lay geographic terms, this was West Oakland, and some areas directly to the east, where the black population was rapidly growing.

The actual redevelopment scheme was simple. The city would buy property in “blighted areas” from slumlords who had been exploiting their tenants and then hand it over to private developers, turning the black residents out into the street. In bulldozing poor people’s homes and handing the land to rich developers, the city could take up to a 50% loss.

Marr was aware that some people would win and some lose in this scheme. The government would buy land at one price, probably not as much as a homeowner would want, and then eat a big chunk of the cost, and hand it to someone else for much less. He called it “squeezing the water out of slum land prices.” Strangely, the point was to use a government agency to depress land values, so that a private developer could come along, rebuild, and take the profits from the rise back up (and presumably beyond) what the government had paid. All taxpayers would subsidize a private interest’s profits. How could that possibly be necessary? The answer, of course, was the power of blight. “Year by year this blight is spreading and sapping Oakland’s economic strength,” he wrote. “Decisive action is necessary to solve this problem once and for all.

At an August City Council meeting to discuss the report, Marr was booed. The council was informed that the Planning Commission had, in fact, rejected his report. In the chaos that played out before an overflowing crowd of hundreds, Councilman Fred Morcom said he was “opposed to putting people out of their houses to make homes for someone else.” As the Tribune put it, “Tumultuous cheers followed Councilman Morcom’s remarks.” The West Oakland Improvement Club, a white group of property owners, delivered a petition opposing the public housing plan with 1,749 signatories who lived or owned inside “the so-called ‘blighted’ area.” Another group, “Property Owners of the Blighted Area,” invoked Soviet Russia. “In the early days of the Russian revolution, Lenin said that to make communism succeed, first destroy the small businessman,” their pamphlet read. “This is the first step in that same direction.”

To be declared blighted was to be stripped of some key property rights while you were also being told, as people understood it, that you lived in a slum or that you were a slumlord. It is not surprising that people did not take kindly to this.

With the room overflowing and demonstrations pushing the meeting out of hand, Mayor Clifford Rishell arranged to continue the meeting the next week at the Oakland Auditorium. It was a time of change for the city government. Led by labor, progressives working through the Oakland Voters League had managed to get a majority on the council, and with the huge influx of war workers, it seemed as if the conservative control of Oakland, epitomized by Joseph Knowland’s Oakland Tribune, might end.

The Oakland Real Estate Board, supported by and as a model for the National Association of Real Estate Boards, went hard at public housing, figuring they could stall President Truman’s ambitious housing plans at the local level. “Public housing is a controversial subject,” Marr told the room. “It always has been and always will be.”

The next week of that August, 3,500 people showed up to the city council meeting. It was the only time that a public meeting had been conducted outside City Hall, and as the Tribune noted, “the audience was by far the largest on record for such an event.” The council was seated on the stage that had hosted the biggest acts to come through Oakland. A standing crowd extended before them, with more citizens packing the risers to the left and right.

Howard Rilea of the West Oakland Improvement Club railed against the project by recalling the earlier bulldozing for Campbell Village and Peralta Villa. “We only have to be stung once,” he said. “Some people are here tonight who lost their homes for a mere pittance to the Federal Government in 1937. It’s high time we called this thing to a halt.” He noted, as many others would, that the price the government might offer him would not allow him to buy a comparable property. And he was white, so imagine how the black homeowners and tenants were feeling. “It might only be worth $1800 to $2000 to the government, but it’s worth a million dollars to me,” he concluded. The head of Oakland’s Real Estate Board went big with his criticism. “Socialized public housing is unAmerican, is contrary to the U.S. Constitution, offers the threat of a socialized state and is a menace to the American voluntary society,” he said. The rest of the anti-housing contingent was composed of various homeowners clubs, apartment house trade groups, the chamber of commerce, and some real estate developers. The very existence of Marr’s report—and the blighted designation it had slapped on the area— “already had caused a loss of millions of dollars in property values”, one realtor argued.

Speaking for the bill, there were various labor groups, a representative of the NAACP, and two men from the most powerful black union, the Brotherhood of Railway and Steamship Clerks.

Through some fancy footwork, the City Council approved the public housing, but only on the condition that it would be built on vacant or public land. The redevelopment report was flat out rejected. West Oakland had been declared blighted, but not officially. Thereafter, papers sometimes referred to the neighborhood as “what some people call the ‘blighted’ area.”

There is an excellent academic analysis of how this report’s public housing provisions shaped local politics in Marilynn S. Johnson’s worthwhile The Second Gold Rush.

1952: Shoreline Development

This unusually intersting report looks at how Oakland’s shoreline—including the port and other kinds of facilities along the water—might develop through the second half of the 20th century. Among other things, the 1952 report states that trade with Asia will play a huge role for Oakland (true) and it suggests the idea for Jack London Square. It’s filled with ideas and is written with much more style than most city reports.

The report tells you how to read it. “This is a thick report. In 89 pages and 11 maps, charts and drawings it describes the master plan for the development of Oakland’s shoreline. But the report is not the master plan,” they write. The master plan is the map which faces page 51. The rest of the book tells the story behind the plan.”

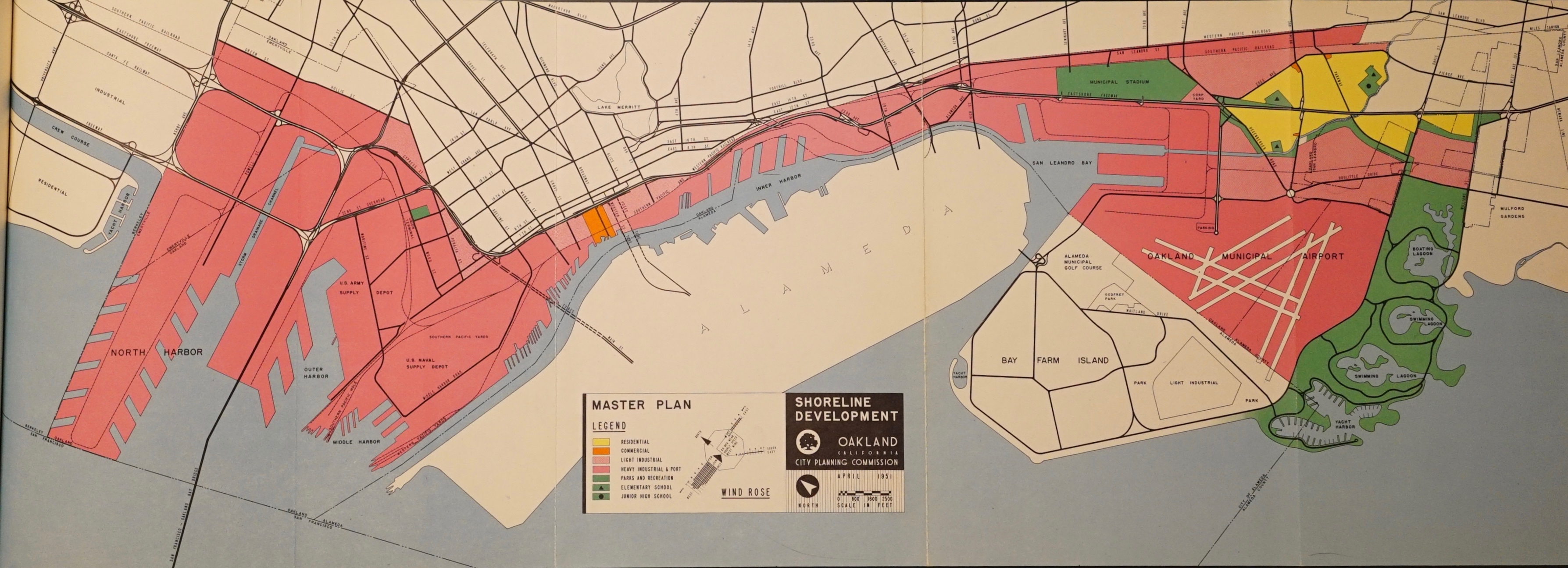

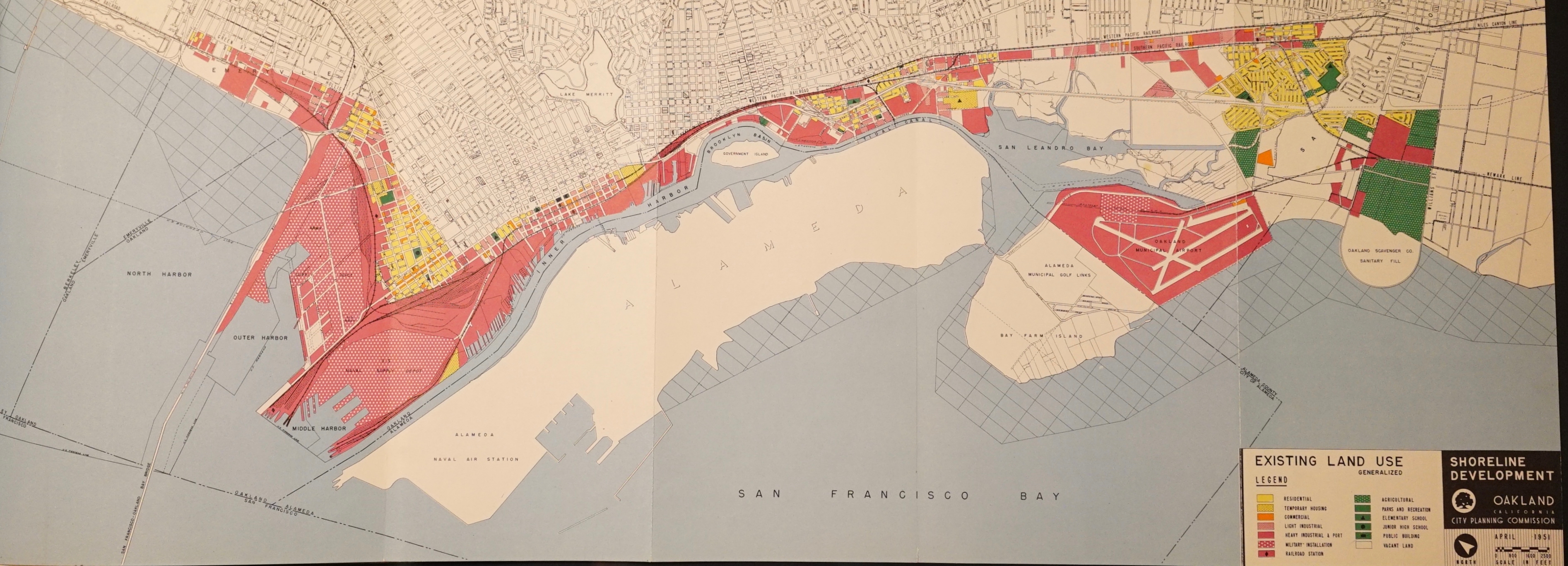

My primary interest in the report is its recommendation that everything west of what’s now Mandela Parkway be made industrial land. As you can see in the map of land use below, Prescott was densely populated, even if industry was interspersed. If this plan had been carried out in full, the neighborhood would, by and large, have been erased.

Meanwhile, way out by the airport, where the Oakland Scavenger Company had a landfill, the city would build a yacht harbor, two swimming lagoons, and a boating lagoon. (In the end, they built the Lew F. Galbraith Golf Course in the 60s, then used it for a dredging dump, then remodeled it into the Metropolitan Golf Links.)

For all this, the report also peered eerily into Oakland’s future as a major port. Up until the late 1960s, Oakland’s port was an afterthought, firmly third in the region behind San Francisco and Richmond. Then came the massive transpacific trade opened up by containerization, which found a home in the industrial land of West Oakland—and new territory created out of Bay. On here, it’s labeled “North Harbor” but we know it now as the Ben E. Nutter Terminal (aka the 7th Street Terminal), which was one of the last huge Bay fill projects before the Bay Area Conservation and Development Commission took over and shut down the filling of the Bay.

And the report nailed why, too. Japan, China, and the other populous countries of Asia.

“China, by virtue of her size and long history of civil disorder, holds the center of the stage in Asia. But the political and economic ferment has spread throughout the continent, involving Indo-China, Indonesia, Thailand, India and even Japan,” we read. “The industrialization of China and the rest of the Orient is late in arriving. Because of its magnitude it will inevitably produce fundamental modifications in the world’s economic and political structure… No one can say exactly what the impact of the industrial revolution in Asia will be on the economy of the Pacific Coast; the potentialities are beyond imagination. Asia’s untapped resources are far greater than Europe’s, and its population is more than half the world’s total. China and Southeast Asia may change swiftly—like Japan and Russia—within half a century, or it may take longer. Much depends upon the world political climate during the transition period. Given an era of peace so that she may concentrate on domestic problems, Asia’s rise may be meteoric.”

From Shoreline Development

The last thing to look at in the report is how it calls for the creation of a “waterfront plaza” at the foot of Broadway, near what would become Jack London Square. The Port of Oakland, apparently, already had this plan. In part because Oakland might have been “the worst town in the country for show business” and East Bay residents might “want to do something more with their evenings than take in an occasional movie and make an annual visit to the Flower Show.”

Around the foot of Broadway, the waterfront has the picturesque, salty atmosphere of an old-time harbor. The mellow, weathered wood of the wharves and piles, the ropes and rigging and the ships passing in the stream suggest the adventure of life at sea and the glamour of foreign ports of call. Already two restaurants are located on the docks where they can capitalize on this unique waterfront atmosphere. Recently the Port of Oakland leased a site for another waterfront restaurant to be called “The Sea Wolf” after Jack London’s well-known novel. London lived in this area as a young man and spent a great deal of his time at Heinhold’s “First and Last Chance,” a saloon established at the foot of Webster Street in the 1880s. Originally a bunkhouse for oyster pirates, the venerable establishment is still in business despite the fact that it is gradually settling at a rakish tilt. The Port has named the block at the foot of Broadway in honor of Jack London and plans to develop the surrounding area as a restaurant center similar to San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf.

From Shoreline Development

And here we are, 67 years later and the Port is finally starting to succeed in making Jack London Square happen.

1956: Residential Area Analysis

This crucial report provided the means to declare areas of Oakland blighted through the use of a “penalty score” developed by city planners. This score was calculated by a convoluted algorithm relying on a variety of factors about the neighborhoods in question. I argue in The Pacific Circuit that this score was actually an index of environmental racism.

The report was covered closely in the Oakland Tribune, which was the mouthpiece of East Bay elites. The urban affairs writer Bill Stokes (later head of BART) used it to say that a huge chunk of the city blighted, including the areas where 98 percent of Oakland’s Black people lived.

Legally, a blight designation could be used to strip some of the property rights from everyone within an area. It was the formal step that was required to initiate the urban renewal that bulldozed thousands of homes in West Oakland.

The formula that was used to calculate the penalty scores is available in Appendix A of the report. It’s worth looking at as an example of how to create a nominally race-blind algorithm that nonetheless allowed city planners to target urban renewal to Black neighborhoods, with disastrous consequences.

1964: Housing Discrimination in Oakland

Sociologist Floyd Hunter was the man who coined the term “power structure” and he came to Oakland to prepare a report on housing discrimination for the Mayor’s Committee on Full Opportunity and the Council of Social Planning in 1963-1964. Hunter’s method, in general, was interview based, and he talked to 60 “brokers, lenders, and social organization personnel,” as well as talking with community organizations in group sessions. In total, Hunter’s people talked with 328 Oaklanders.

What emerges in this short report of the findings is … that yes, white Oakland was racist and discrimination was rampant. The way it was usually played was that 60 percent of white Oaklanders were racist and one third of them would discriminate in housing. None of this was a surprise to black residents, or should have be a surprise to anyone who has looked at the documents above this one.

The report uses plain language to describe the economics of the ghetto, especially how it benefitted white property owners. Let a building run down, but keep cramming black people who needed housing into it, and you could make a lot of money. “Properties, that had long since paid out their original investment values, continued to pay and repay their owners handsome inflationary and speculative gains,” the report states. “Real property became the rare American commodity that could physically depreciate and at the same time financially appreciate.”

The report sums up the prejudice that the researchers encountered, like this list of stereotypes about black people:

“Out of selfish interest, guilt, self-justification, fear, ignorance and prejudice, Many came to believe that the plight of the Negro was his own doing. They believed that the deterioration of the neighborhoods in which he lived was his fault. They believed that he disorder and privation were somehow inherent in the character makeup of the Negro. They believed that cultural traits of earlier rural Negro migrants were retained intact by on-coming, city-born generations. They believed themselves to be different and superior.”

And it also documents how angry a lot of white people were that black people had the audacity to move to their town (incentivized by the U.S. government and pushed by equally racist, but more more openly violent southerners).

“The reactions of many Caucasians to this population upsurge has been a mixture of physical flight, psychological withdrawal, and shame. To them, the image of Oakland has been tainted beyond redemption. There is much head shaking disapproval about what is considered a hopeless situation. And in some cases there is implacable and open rejection of the Negro as a citizen. “Send them back to Africa,” said one of these. “I would not help them one bit to improve their lot here,” said another, “to do so would only encourage another horde to descend from the south upon the community.” And in a half whisper: “Did you know that Oakland has been designated as the West Coast colored capital? Within another five years the whole city will be black. Not a member of the city council will be white.”

Housing Discrimination in Oakland, Floyd Hunter

The report also has reflects on the regional dynamics that saw the black population in Oakland boom. “From the metropolitan point of view, the area shown was filled since 1945, in part, by Negroes who had been displaced in Richmond, Berkeley, Albany, and the city of Alameda following the destruction in those communities of temporary war housing,” we read. “These communities were determined to rid themselves of large surplus Negro labor forces. Those made homeless became, in many instances, relief refugees in Oakland.”

It describes the position that metropolitan forces took towards black people as one of “containment,” drawing on the language of the Cold War: “Thus, one may see that the pattern, city by city, in the San Francisco Bay Area was that of containment of Negro populations within restricted areas, and in some instances forcing them to move from community to community. As one factor among many, the pressures generated in containment and forced migration have caused various individual and group reactions and explosions, culminated by 1964 in various equality marches and sit-ins metropolitan-wide.”

The report was received by the city government. The Oakland Tribune gave it very straight front page treatment on July 28, 1964. By September, it was being referred to as “controversial” and there were accusations it was being suppressed, though it does not appear that, technically, it was.

(One note on the document. It comes courtesy of the African American Library and Museum, and I think I obtained and scanned it all, but it’s clearly not the entire report, so it must have been excerpted at some point. Nonetheless, the main points are clear.)

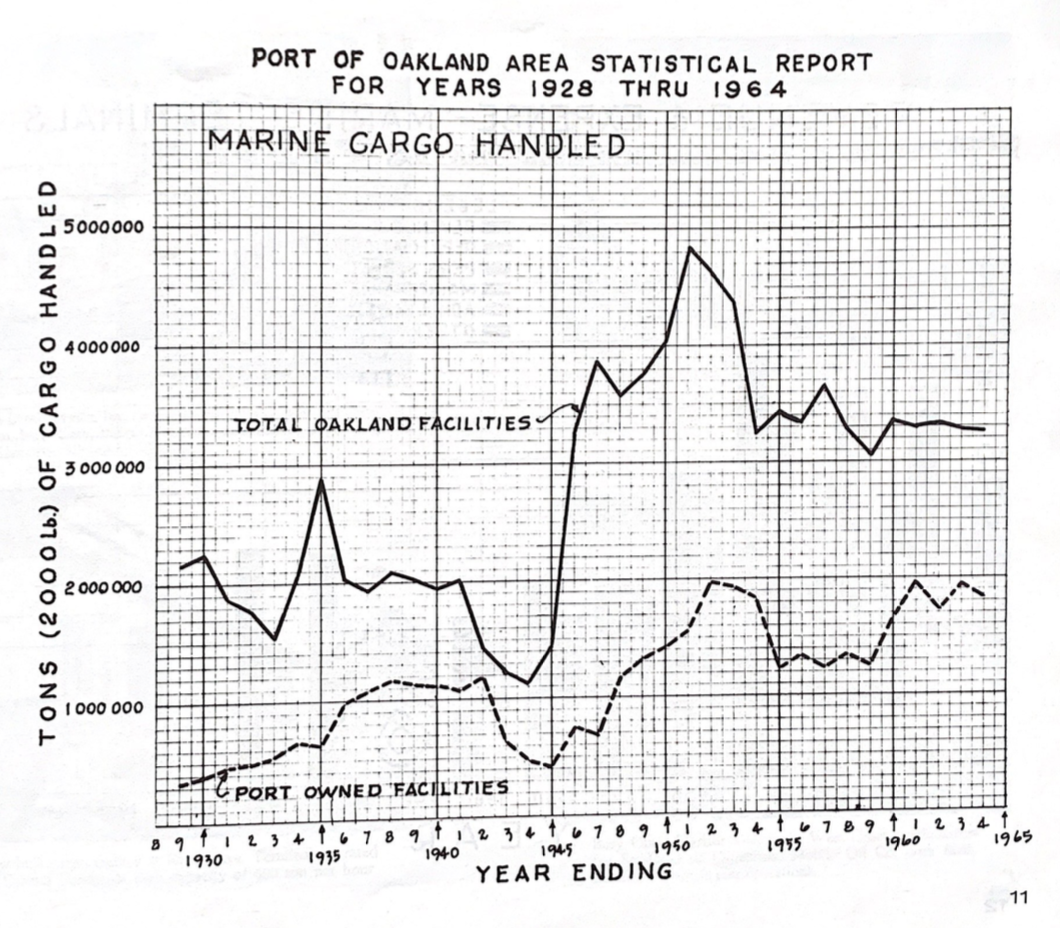

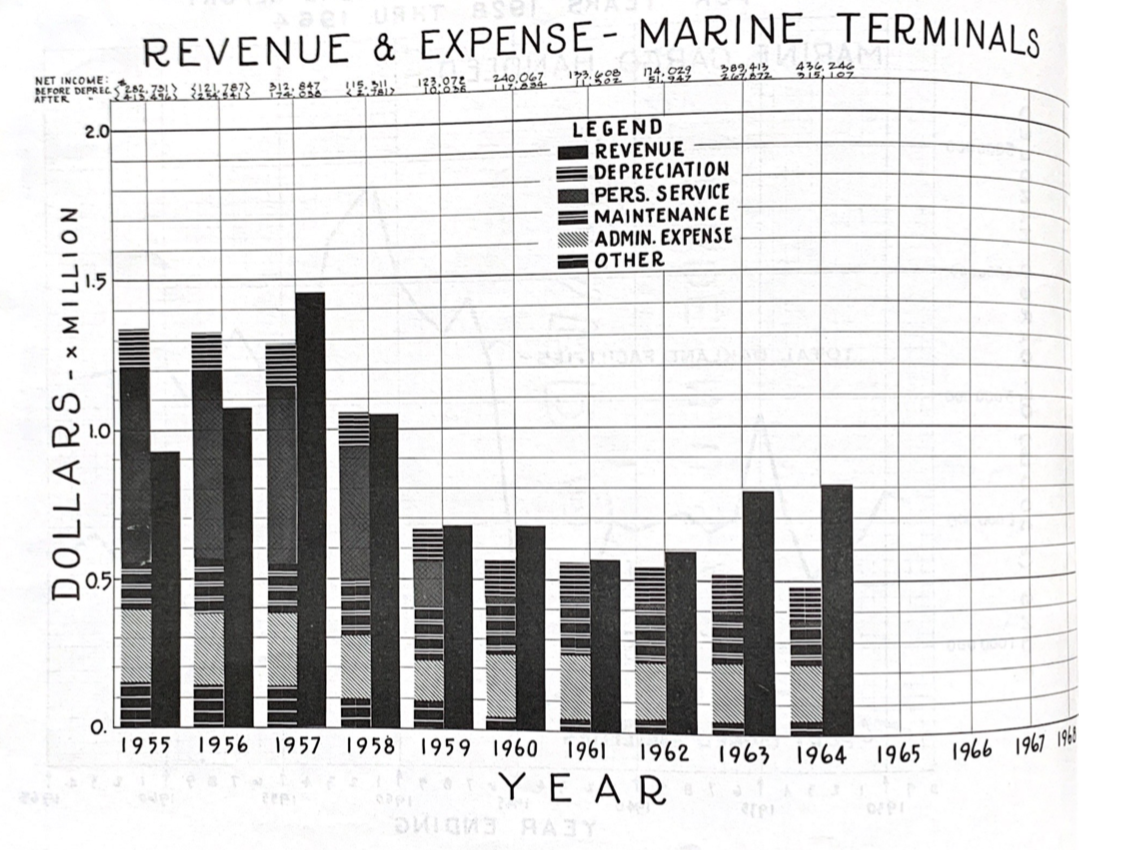

1964: Port of Oakland Annual Report

This annual report captures the Port of Oakland right before it explodes into one of the world’s major ports. Long overshadowed by San Francisco and even Richmond, just in the Bay Area, Oakland had primarily been an agricultural export terminal. But that was before SeaLand, the first successful container shipping company, made Oakland its West Coast headquarters in 1962. And then the intensifying Vietnam War guaranteed the company profitability on its Pacific routes.

Within just a few years, the Port of Oakland would eclipse San Francisco and almost all other container shipping ports as this mechanized version of cargo handling took over the industry. It replaced breakbulk cargo, in which many different types of goods were stored in different holds inside a ship. The Port planned for its success, but it also got lucky, as Oakland was a much more natural place for container shipping, which requires many acres of yards, as well as easy access to railroads and highways.

The adjacency of military facilities to the Port of Oakland’s commercial operations also seemed to have helped spark the “spectacular increase” in SeaLand’s business, which partially offset the loss of barge traffic to new oil pipelines.

This report also contains basic financial data about the Port as well as its plans for Jack London Square and the airport.

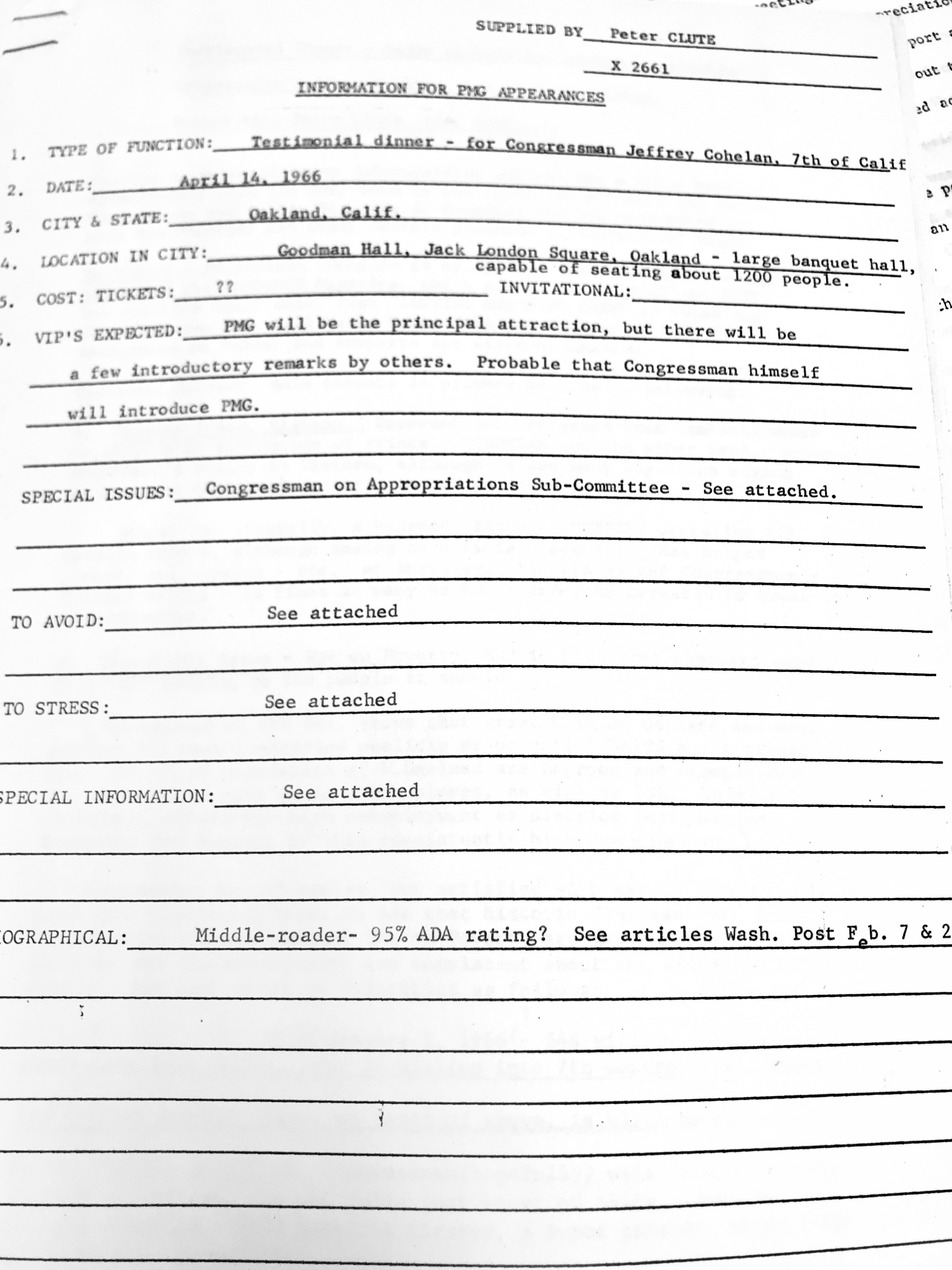

1966: Internal Postal Service Memos About Oakland’s New Post Office

These documents are an unusual and revealing look inside the sausagemaking of Lyndon Johnson’s administration as the wars on poverty and in Vietnam raged. They show an unvarnished political look at the district from the middle ranks of the Johnson administration, as well as commenting directly on the huge post office distribution center which was just then getting under way on 7th Street, after sitting empty for seven years after the demolition of the homes in the neighborhood. These documents were meant to prepare Postmaster General Larry O’Brien for a trip out to Oakland for a dinner with Congressman Jeffrey Cohelan.

If this does not exactly sound like a recipe for drama, remember that until 1971, the Postmaster General was a member of the President’s cabinet! As such, they were as much a political player as any secretary of state. In fact, because the Post Office was (and is) a large source of jobs, the Postmaster General was a powerful position. So, what you see in these documents, which I obtained from the archives of the United States Postal Service, is the sort of memo that a political staff might prepare for a politician. What was going on in the place? What were the hot button topics that might be bringing Cohelan (or O’Brien) grief? It’s unguarded, and consequently, hilarious.

Cohelan, we read, was a loyal Johnson ally in Congress, who was now the Democratic facing off against a new leftist challenger, Robert Scheer, the editor of the magazine Ramparts. Here’s how Cohelan’s opponent is described: “Scheer is, literally a bearded far-out LEFTIST, operating off Berkeley campus, although having no official capacity. Has helped picket, stop trains – etc. – in Berkeley.”

Cohelan represented the 7th District, which the report says, “has been identified publicly as potential WATTS and a tinder box. 25-30% of population of W. Oakland are Negroes and unemployment is 2 to 7 times as much as other places, as high as 30%.” It also notes that $6 million of War on Poverty money had flowed into the district while admitting that the “historic” effort to aid the poor needed “more vigorous efforts.”

The Congressman would face a Republican opponent named Malcolm Chaplin, and as with Scheer, the memo pulls no punches, saying he “falls just short of being a John Bircher, Malcolm CHAMPLIN – 200% American firster, super patriot, waves flags of Communism and morality.” As such, the report dryly notes, “Cohelan, then, won’t swing far left in primary.”

A second memo details the new post office facility in the local political context. “Oakland’s civic atmosphere is reportedly extremely tense: the Mayor is understood to be resigning and the Chief of Police has already done so.” The Mayor was John Houlihan, who did resign, and was subsequently convicted of embezzling from a widowwhile he was mayor. (Reagan, a fellow Republican, pardoned him.)

Then, the next section is one of the strangest I’ve ever encountered. Here’s what it says. It begins ordinarily enough: “Contract Compliance Examiner Vernon Strange suggests caution against possibility that demonstrations may be organized along the route of the PMG if extensive publicity is given to Mr. O’Brien’s program for the California trip.”

But then, it admits that the prime contractor on the new post office building, S.S. Silverblatt “professes an affirmative position on equal opportunity but shows little in practice.” And then, astonishingly, credits this employee of the post office with preventing a riot! “Examiner Strange’s contacts so far — not knowing who will do actual construction work on the project — have been with building trades’ unions and community organizations, such as NAACP and CORE [Congress of Racial Equality]. His groundwork has probably been preventing a Watts-Type uprising and possible repetition of St. Louis Arch problem.”

It references a “report of Examiner Strange” but that was not kept in the postal service files. One can only wonder what old Examiner Strange was up to to have such presumed impact. (And if you’re curious about the “St. Louis Arch problem” — a discrimination dispute broke out between the Johnson administration and AFL-CIO in the construction of a visitor center when a black plumber showed up to the job site.)

After that bombshell, the report returns to the nuts-and-bolts of the construction of the huge postal distribution center. The capabilities and needs of the various postal facilities in the Bay are recounted.

As for Cohelan, he did eventually lose his seat and for reasons related to Vietnam and the War on Poverty. But Scheer didn’t beat him. In 1971, Cohelan lost to Ron Dellums, a veteran of the Bayview Hunters Point Youth Opportunity Center and nephew of C.L. Dellums, who was a powerful mid-century union (and civil rights) leader in Oakland with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids. Dellums held the office until 1998.